Implement with jsfiddle so people can see the specs and their code in the same window rather than a combo of editor/browser

SpecRunner.html in your web browserrecursion.jsspec/part1.js and

spec/part2.js as necessary

Recursion is when a function calls itself until it doesn’t. –not helpful person

Is it a true definition? Mostly. Recursion is when a function calls itself. A recursive function can call itself forever, but that’s generally not preferred. It’s often a good idea to include a condition in the function definition that allows it to stop calling itself. This condition is referred to as a base case. As a general rule, recursion shouldn’t be utilized without an accompanying base case unless an infinite operation is desired. This leaves us with two fundamental conditions every recursive function should include:

base case

recursive case

What does this all mean? Let’s consider a silly example:

function stepsToZero(n) {

if (n === 0) {

/* base case */

return "Reached zero";

} else {

/* recursive case */

console.log(n + " is not zero");

return stepsToZero(n - 1);

}

}

This function doesn’t do anything meaningful, but hopefully it

demonstrates the fundamental idea behind recursion. Simply put, recursion

provides us a looping or repeating mechanism. It repeats an operation

until a base condition is met. Let’s step through an

invocation of the above function to see how it evaluates.

stepsToZero(n) where n is the number

2

Invoke stepsToZero(n-1) where n-1 evaluates

to 1

Every recursive call adds a new invocation to the stack on top of the previous invocation

stepsToZero(n-1) where n-1 evaluates to

0

Return out of the initial invocation

Note that the value returned from the base case (step 9) gets returned to the previous invocation (step 4) on the stack. Step 4’s invocation takes that value and returns it to the invocation that preceded it (step 1). Once the initial invocation is reached, it returns the value to whatever invoked it. Through these steps, you can watch the call stack build up and once the base case is reached, the return value is passed back down as each invocation pops off the stack.

Due to the way the execution stack operates, it’s as if each function invocation pauses in time when a recursive call is made. The function that pauses before a recursive call will resume once the recursive call completes. If you’ve seen the movie Inception, this model may sound reminiscent to when the characters enter a person’s dreams and time slowed. The difference is time doesn’t actually slow with recursive invocations; rather, it’s a matter of order of operations. If a new invocation enters the execution stack, that invocation must complete before the previous can continue and complete.

Recursion can be elegant, but it can also be dangerous. In some cases, recursion feels like a more natural and readable solution; in others, it ends up being contrived. In most cases, recursion can be avoided entirely and sometimes should in order to minimize the possibility of exceeding the call stack and crashing your app. But keep in mind that code readability is important. If a recursive solution reads more naturally, then it may be the best solution for the given problem.

Recursion isn’t unique to any one programming language. As a software engineer, you will encounter recursion and it’s important to understand what’s happening and how to work with it. It’s also important to understand why someone might use it. Recursion is often used when the depth of a thing is unknown or every element of a thing needs to be touched. For example, you might use recursion if you want to find all DOM elements with a specific class name. You may not know how deep the DOM goes and need to touch every element so that none are missed. The same can be said for traversing any structure where all possible paths need to be considered and investigated.

Recursion is often used in divide and conquer algorithms where problems can be divided into similar subproblems and conquered individually. Consider traversing a tree structure. Each branch may have its own “children” branches. Every branch is essentially just another tree which means, as long as child trees are found, we can recurse on each child.

What’s the difference and connections between recursion, divide-and-conquer algorithm, dynamic programming, and greedy algorithm? If you haven’t made it clear. Doesn’t matter! I would give you a brief introduction to kick off this section.

What’s the difference and connections between recursion, divide-and-conquer algorithm, dynamic programming, and greedy algorithm? If you haven’t made it clear. Doesn’t matter! I would give you a brief introduction to kick off this section.

Recursion is a programming technique. It’s a way of thinking about solving problems. There’re two algorithmic ideas to solve specific problems: divide-and-conquer algorithm and dynamic programming. They’re largely based on recursive thinking (although the final version of dynamic programming is rarely recursive, the problem-solving idea is still inseparable from recursion). There’s also an algorithmic idea called greedy algorithm which can efficiently solve some more special problems. And it’s a subset of dynamic programming algorithms.

The divide-and-conquer algorithm will be explained in this section. Taking the most classic merge sort as an example, it continuously divides the unsorted array into smaller sub-problems. This is the origin of the word divide and conquer. Obviously, the sub-problems decomposed by the ranking problem are non-repeating. If some of the sub-problems after decomposition are duplicated (the nature of overlapping sub-problems), then the dynamic programming algorithm is used to solve them!

.

├── AUX_MATERIALS

│ ├── recursion-flow.PNG

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── sandbox

│ │ ├── LOs.js

│ │ ├── example2.js

│ │ ├── examples.js

│ │ ├── exponent.js

│ │ ├── factorial.js

│ │ ├── fibonacci.js

│ │ ├── flatten.js

│ │ ├── memoize.js

│ │ ├── recursiveCallStack.js

│ │ ├── recursiveIsEven.js

│ │ ├── recursiveRange.js

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ ├── sum.js

│ │ └── tabulate.js

│ ├── solved.pdf

│ └── unzolved.pdf

├── README.html

├── README.md

├── blank

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── SpecRunner.html

│ ├── lib

│ │ ├── chai.js

│ │ ├── css

│ │ │ ├── mocha.css

│ │ │ └── right.html

│ │ ├── jquery.js

│ │ ├── mocha.js

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ ├── sinon.js

│ │ └── testSupport.js

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── spec

│ │ ├── part1.js

│ │ ├── part2.js

│ │ └── right.html

│ ├── src

│ │ ├── recursion.js

│ │ └── right.html

│ └── testing

│ ├── directory1.html

│ ├── left1.html

│ ├── prism.css

│ ├── prism.js

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── right1.html

│ └── starter.html

├── dir.md

├── directory.html

├── images

│ ├── BubbleSort.gif

│ ├── InsertionSort.gif

│ ├── MergeSort.gif

│ ├── QuickSort.gif

│ ├── SLL-diagram.png

│ ├── SelectionSort.gif

│ ├── array-in-memory.png

│ ├── fib_memoized.png

│ ├── fib_tree.png

│ ├── fib_tree_duplicates.png

│ ├── github-repo-menu-bar-wiki.png

│ └── right.html

├── index.html

├── left.html

├── my-solutions

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── SpecRunner.html

│ ├── complete.html

│ ├── lib

│ │ ├── chai.js

│ │ ├── css

│ │ │ ├── mocha.css

│ │ │ └── right.html

│ │ ├── jquery.js

│ │ ├── mocha.js

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ ├── sinon.js

│ │ └── testSupport.js

│ ├── prism.css

│ ├── prism.js

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── spec

│ │ ├── part1.js

│ │ ├── part2.js

│ │ └── right.html

│ ├── src

│ │ ├── recursion.js

│ │ └── right.html

│ └── style.css

├── part-2

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── SpecRunner.html

│ ├── lib

│ │ ├── jasmine-1.0.0

│ │ │ ├── MIT.LICENSE

│ │ │ ├── jasmine-html.js

│ │ │ ├── jasmine.css

│ │ │ ├── jasmine.js

│ │ │ └── right.html

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ └── underscore.js

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── solutions

│ │ ├── binarySearchTree.js

│ │ ├── hashTable.js

│ │ ├── hashTableHelpers.js

│ │ ├── linkedList.js

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ ├── set.js

│ │ └── tree.js

│ ├── spec

│ │ ├── binarySearchTreeSpec.js

│ │ ├── hashTableSpec.js

│ │ ├── linkedListSpec.js

│ │ ├── right.html

│ │ ├── setSpec.js

│ │ └── treeSpec.js

│ └── src

│ ├── binarySearchTree.js

│ ├── hashTable.js

│ ├── hashTableHelpers.js

│ ├── linkedList.js

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── set.js

│ └── tree.js

├── prism.css

├── prism.js

├── right.html

├── style.css

├── tabs

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── tabs.html

│ ├── tabs2.html

│ └── template-files

│ ├── LmfE5ZMlM8QjZWyylbaJdeYzodpJKK3mlCt6sCr3jaw.js

│ ├── about-us-page-template.jpg

│ ├── ad_status.js

│ ├── agency-template.jpg

│ ├── analytics.js

│ ├── application-template.jpg

│ ├── article-template.jpg

│ ├── base.js

│ ├── best-bootstrap-templates-492x492.jpg

│ ├── blog.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-basic-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-ecommerce-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-grid.min.css

│ ├── bootstrap-landing-page-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-layout-templates-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-login-page-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-one-page-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-page-templates-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-portfolio-template-600x600.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-reboot.min.css

│ ├── bootstrap-responsive-website-templates-600x600.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-sample-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-single-page-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-starter-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-templates-examples-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap-theme-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── bootstrap.min.css

│ ├── bootstrap.min.js

│ ├── business-template.jpg

│ ├── carousel-template.jpg

│ ├── cast_sender.js

│ ├── coming-soon-template.jpg

│ ├── contact-form-template-1.jpg

│ ├── corporate-template.jpg

│ ├── documentation-template.jpg

│ ├── download-bootstrap-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── education-template.jpg

│ ├── embed.js

│ ├── error-template.jpg

│ ├── event-template.jpg

│ ├── f(1).txt

│ ├── f.txt

│ ├── faq-template.jpg

│ ├── fbevents.js

│ ├── fetch-polyfill.js

│ ├── footer-template.jpg

│ ├── form-templates.jpg

│ ├── free-html5-bootstrap-templates-600x600.jpg

│ ├── gallery-template.jpg

│ ├── google-maps-template.jpg

│ ├── grid-template.jpg

│ ├── gtm.js

│ ├── hGaQaBeUfGw.html

│ ├── header-template.jpg

│ ├── homepage-template.jpg

│ ├── hotel-template.jpg

│ ├── jarallax.min.js

│ ├── jquery.min.js

│ ├── jquery.touch-swipe.min.js

│ ├── landing-page-template.jpg

│ ├── list-template.jpg

│ ├── magazine-template.jpg

│ ├── map-template.jpg

│ ├── mbr-additional.css

│ ├── menu-template.jpg

│ ├── mobirise-icons.css

│ ├── multi-page-template.jpg

│ ├── navbar-template.jpg

│ ├── navigation-menu.jpg

│ ├── news-template.jpg

│ ├── one-page-1.jpg

│ ├── ootstrap-design-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── parallax-scrolling-template.jpg

│ ├── parallax-template.jpg

│ ├── personal-website-template.jpg

│ ├── photo-gallery-template.jpg

│ ├── photography-template.jpg

│ ├── popper.min.js

│ ├── premium-bootstrap-templates-492x492.jpg

│ ├── profile-template.jpg

│ ├── real-estate-template.jpg

│ ├── registration-form-template.jpg

│ ├── remote.js

│ ├── restaurant-template.jpg

│ ├── right.html

│ ├── script.js

│ ├── script.min.js

│ ├── shopping-cart.jpg

│ ├── simple-bootstrap-template-492x492.jpg

│ ├── slider-template.jpg

│ ├── slider.jpg

│ ├── smooth-scroll.js

│ ├── social-network-template.jpg

│ ├── store-template.jpg

│ ├── style(1).css

│ ├── style.css

│ ├── tab-template.jpg

│ ├── table-template.jpg

│ ├── tether.min.css

│ ├── tether.min.js

│ ├── travel-template.jpg

│ ├── video-bg-template.jpg

│ ├── video-bg.jpg

│ ├── video-gallery-template.jpg

│ ├── video-template.jpg

│ ├── warren-wong-200912-2000x1304.jpg

│ ├── web-application-template.jpg

│ ├── wedding-template.jpg

│ ├── www-embed-player.js

│ └── www-player-webp.css

└── tree.md

22 directories, 227 files

Before introducing divide and conquer algorithm, we must first understand the concept of recursion.

The basic idea of recursion is that a function calls itself directly or indirectly, which transforms the solution of the original problem into many smaller sub-problems of the same nature. All we need is to focus on how to divide the original problem into qualified sub-problems, rather than study how this sub-problem is solved. The difference between recursion and enumeration is that enumeration divides the problem horizontally and then solves the sub-problems one by one, but recursion divides the problem vertically and then solves the sub-problems hierarchily.

The following illustrates my understanding of recursion. If you don’t want to read, please just remember how to answer these questions:

Two of the most important characteristics of recursive code: end conditions and self-invocation. Self-invocation is aimed at solving sub-problems, and the end condition defines the answer to the simplest sub-problem.

Actually think about it, what is the most successful application of recursion? I think it’s mathematical induction. Most of us learned mathematical induction in high school. The usage scenario is probably: we can’t figure out a summation formula, but we tried a few small numbers which seemed containing a kinda law, and then we compiled a formula. We ourselves think it shall be the correct answer. However, mathematics is very rigorous. Even if you’ve tried 10,000 cases which are correct, can you guarantee the 10001th correct? This requires mathematical induction to exert its power. Assuming that the formula we compiled is true at the kth number, furthermore if it is proved correct at the k + 1th, then the formula we have compiled is verified correct.

So what is the connection between mathematical induction and recursion? We just said that the recursive code must have an end condition. If not, it will fall into endless self-calling hell until the memory exhausted. The difficulty of mathematical proof is that you can try to have a finite number of cases, but it is difficult to extend your conclusion to infinity. Here you can see the connection-infinite.

The essence of recursive code is to call itself to solve smaller sub-problems until the end condition is reached. The reason why mathematical induction is useful is to continuously increase our guess by one, and expand the size of the conclusion, without end condition. So by extending the conclusion to infinity, the proof of the correctness of the guess is completed.

First to train the ability to think reversely. Recursive thinking is the thinking of normal people, always looking at the problems in front of them and thinking about solutions, and the solution is the future tense; Recursive thinking forces us to think reversely, see the end of the problem, and treat the problem-solving process as the past tense.

Second, practice analyzing the structure of the problem. When the problem can be broken down into sub problems of the same structure, you can acutely find this feature, and then solve it efficiently.

Third, go beyond the details and look at the problem as a whole. Let’s talk about merge and sort. In fact, you can divide the left and right areas without recursion, but the cost is that the code is extremely difficult to understand. Take a look at the code below (merge sorting will be described later. You can understand the meaning here, and appreciate the beauty of recursion).

void sort(Comparable[] a){

int N = a.length;

// So complicated! It shows disrespect for sorting. I refuse to study such code.

for (int sz = 1; sz < N; sz = sz + sz)

for (int lo = 0; lo < N - sz; lo += sz + sz)

merge(a, lo, lo + sz - 1, Math.min(lo + sz + sz - 1, N - 1));

}

/* I prefer recursion, simple and beautiful */

void sort(Comparable[] a, int lo, int hi) {

if (lo >= hi) return;

int mid = lo + (hi - lo) / 2;

sort(a, lo, mid); // soft left part

sort(a, mid + 1, hi); // soft right part

merge(a, lo, mid, hi); // merge the two sides

}Looks simple and beautiful is one aspect, the key is very interpretable: sort the left half, sort the right half, and finally merge the two sides. The non-recursive version looks unintelligible, full of various incomprehensible boundary calculation details, is particularly prone to bugs and difficult to debug. Life is short, i prefer the recursive version.

Obviously, sometimes recursive processing is efficient, such as merge sort, sometimes inefficient, such as counting the hair of Monkey King, because the stack consumes extra space but simple inference does not consume space. Example below gives a linked list header and calculate its length:

My point of view: Understand what a function does and believe it can accomplish this task. Don’t try to jump into the details. Do not jump into this function to try to explore more details, otherwise you will fall into infinite details and cannot extricate yourself. The human brain carries tiny sized stack!

Let’s start with the simplest example: traversing a binary tree.

Above few lines of code are enough to wipe out any binary tree. What I

want to say is that for the recursive function

traverse (root) , we just need to believe: give it a root

node root , and it can traverse the whole tree. Since this

function is written for this specific purpose, so we just need to dump the

left and right nodes of this node to this function, because I believe it

can surely complete the task. What about traversing an N-fork tree? It’s

too simple, exactly the same as a binary tree!

As for pre-order, mid-order, post-order traversal, they are all obvious. For N-fork tree, there is obviously no in-order traversal.

The following explains a problem from LeetCode in detail: Given a binary tree and a target value, the values in every node is positive or negative, return the number of paths in the tree that are equal to the target value, let you write the pathSum function:

The problem may seem complicated, but the code is extremely concise, which is the charm of recursion. Let me briefly summarize the solution process of this problem:

First of all, it is clear that to solve the problem of recursive tree, you must traverse the entire tree. So the traversal framework of the binary tree (recursively calling the function itself on the left and right children) must appear in the main function pathSum. And then, what should they do for each node? They should see how many eligible paths they and their little children have under their feet. Well, this question is clear.

According to the techniques mentioned earlier, define what each recursive function should do based on the analysis just now:

PathSum function: Give it a node and a target value. It returns the total number of paths in the tree rooted at this node and the target value.

Count function: Give it a node and a target value. It returns a tree rooted at this node, and can make up the total number of paths starting with the node and the target value.

/* With above tips, comment out the code in detail */

int pathSum(TreeNode root, int sum) {

if (root == null) return 0;

int pathImLeading = count(root, sum); // Number of paths beginning with itself

int leftPathSum = pathSum(root.left, sum); // The total number of paths on the left (Believe he can figure it out)

int rightPathSum = pathSum(root.right, sum); // The total number of paths on the right (Believe he can figure it out)

return leftPathSum + rightPathSum + pathImLeading;

}

int count(TreeNode node, int sum) {

if (node == null) return 0;

// Can I stand on my own as a separate path?

int isMe = (node.val == sum) ? 1 : 0;

// Left brother, how many sum-node.val can you put together?

int leftBrother = count(node.left, sum - node.val);

// Right brother, how many sum-node.val can you put together?

int rightBrother = count(node.right, sum - node.val);

return isMe + leftBrother + rightBrother; // all count i can make up

}Again, understand what each function can do and trust that they can do it.

In summary, the binary tree traversal framework provided by the PathSum function calls the count function for each node during the traversal. Can you see the pre-order traversal (the order is the same for this question)? The count function is also a binary tree traversal, used to find the target value path starting with this node. Understand it deeply!

Merge and sort, typical divide-and-conquer algorithm; divide-and-conquer, typical recursive structure.

The divide-and-conquer algorithm can go in three steps: decomposition-> solve-> merge

To merge and sort, let’s call this function merge_sort .

According to what we said above, we must clarify the responsibility of the

function, that is, sort an incoming array. OK, can this

problem be solved? Of course! Sorting an array is just the same to sorting

the two halves of the array separately, and then merging the two halves.

Well, this algorithm is like this, there is no difficulty at all. Remember

what I said before, believe in the function’s ability, and pass it to him

half of the array, then the half of the array is already sorted. Have you

found it’s a binary tree traversal template? Why it is postorder

traversal? Because the routine of our divide-and-conquer algorithm is

decomposition-> solve (bottom)-> merge (backtracking)

Ah, first left and right decomposition, and then processing merge,

backtracking is popping stack, which is equivalent to post-order

traversal. As for the merge function, referring to the

merging of two ordered linked lists, they are exactly the same, and the

code is directly posted below.

Let’s refer to the Java code in book Algorithm 4 below, which

is pretty. This shows that not only algorithmic thinking is important, but

coding skills are also very important! Think more and imitate more.

public class Merge {

// Do not construct new arrays in the merge function, because the merge function will be called multiple times, affecting performance.Construct a large enough array directly at once, concise and efficient.

private static Comparable[] aux;

public static void sort(Comparable[] a) {

aux = new Comparable[a.length];

sort(a, 0, a.length - 1);

}

private static void sort(Comparable[] a, int lo, int hi) {

if (lo >= hi) return;

int mid = lo + (hi - lo) / 2;

sort(a, lo, mid);

sort(a, mid + 1, hi);

merge(a, lo, mid, hi);

}

private static void merge(Comparable[] a, int lo, int mid, int hi) {

int i = lo, j = mid + 1;

for (int k = lo; k <= hi; k++)

aux[k] = a[k];

for (int k = lo; k <= hi; k++) {

if (i > mid) { a[k] = aux[j++]; }

else if (j > hi) { a[k] = aux[i++]; }

else if (less(aux[j], aux[i])) { a[k] = aux[j++]; }

else { a[k] = aux[i++]; }

}

}

private static boolean less(Comparable v, Comparable w) {

return v.compareTo(w) < 0;

}

}LeetCode has a special exercise of the divide-and-conquer algorithm. Copy the link below to web browser and have a try:

https://leetcode.com/tag/divide-and-conquer/

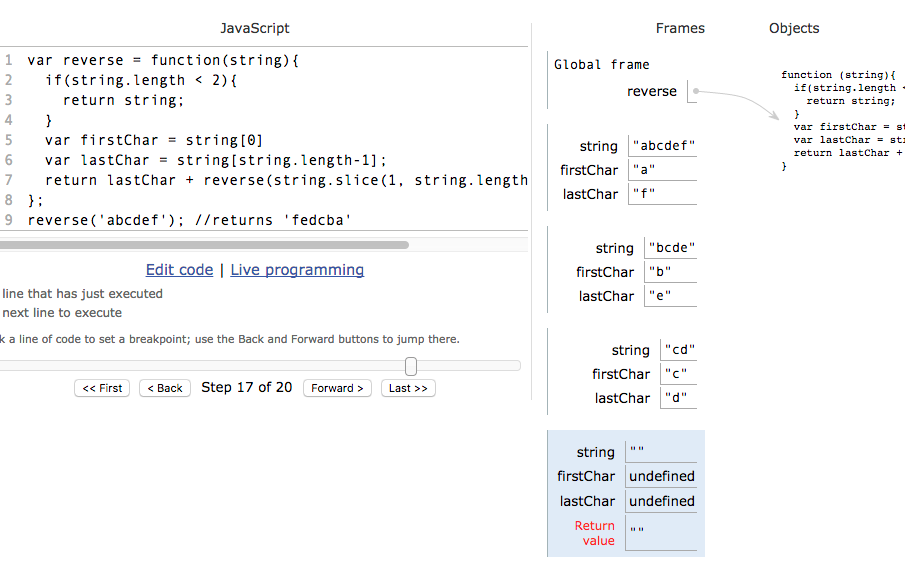

Prompt: write a function that will reverse a string:

var reverse = function(string){

if(string.length < 2){

}

var first = string[0]

var last = string[string.length-1]; return last +reverse(string.slice(1,

string.length-1)) + first; }; reverse(‘abcdef’); //returns ‘fedcba’

//explain what a recursive function is

A function that calls itself is a recursive function.

If a function calls itself… then that function calls itself… then that function calls itself… well… then we have fallen into an infinite loop (a very unproductive place to be). To benefit from recursive calls, we need to be careful to include to give our interpreter a way to break out of the cycle of recursive function calls; we call this a base case.

The base case in the solution code above is as simple as testing that the length of the argument is less than 2… and if it is, returning the the value of that argument.

Notice how each time we recursively call the reverse function, we are passing it a shorter string argument… so each recursive call is getting us closer to hitting our base case.

//visualize the interpreter’s path through recursive function calls

Image for post

Image for post

Slow down and follow the interpreter through its execution of your algorithm (thanks to PythonTutor.com)

Python Tutor is an excellent resource for learning to visualize and trace variable values through the multiple execution contexts of a recursive function’s invocation.

Try it now with these simple steps:

//when can a recursive function help me?

So if I hope that at this point that you are thinking: there is a better way to reverse a function, or there is a simpler way to reverse a string…

First off… simpler is better. Writing good code isn’t about being clever or fancy; good code is about writing code that works, that makes sense to as many other minds as possible, that is time efficient, and that is memory efficient (in order of importance). As new programers, the first of these criteria is obvious, and the last two are given way too much weight. It’s the second of these criteria that needs to carry much more weight in our minds and deserves the most attention. Recursive functions can be a powerful tool in helping us write clear and simple solutions.

To be clear: recursion is not about being fancy or clever… it is an important skill to wrestle with early because there will be many scenarios when employing recursion will allow for a simpler and more reliable solution than would be possible without recursive functions.

//more useful example

Prompt: check to see if a binary-search-tree contains a value

var searchBST = function(tree, num){

if(tree.val === num){

} else if(num > tree.val){

} else{

}

}; var tree = {val: 9,

searchBST(tree, 4) // return falseWhen traversing trees and many other other non-primative data structures, recursion allows us to define a clear algorithm that elegantly handles uncertainty and complexity. Without recursion, it would be impossible to write a single function that could search a binary search tree of any size and state… yet by employing recursion, we can write a concise algorithm that will traverse any binary search tree and determine if it contains a value or not.

Take a moment to analyze how recursion is used in this example by tracing the interpreters path through this solution. Just as we did for the reverse function above, paste this binary search tree code snippet into the editor at http://pythontutor.com/javascript.html#mode=display

In this function definition, there are three base cases that will return a value instead of recursively calling the searchBST function… can you find them?

//now go practice using recursion

Big O Memoization And Tabulation - Recursion Videos - Curating Complexity: A Guide to Big-O Notation - Why Big-O? - Big-O Notation - Common Complexity Classes - The seven major classes - Memoization - Memoizing factorial - Memoizing the Fibonacci generator - The memoization formula - Tabulation - Tabulating the Fibonacci number - Aside: Refactoring for O(1) Space - Analysis of Linear Search - Analysis of Binary Search - Analysis of the Merge Sort - Analysis of Bubble Sort - LeetCode.com - Memoization Problems - Tabulation Problems

Sorting Algorithms - Bubble Sort - “But…then…why are we…” - The algorithm bubbles up - How does a pass of Bubble Sort work? - Ending the Bubble Sort - Pseudocode for Bubble Sort - Selection Sort - The algorithm: select the next smallest - The pseudocode - Insertion Sort - The algorithm: insert into the sorted region - The Steps - The pseudocode - Merge Sort - The algorithm: divide and conquer - Quick Sort - How does it work? - The algorithm: divide and conquer - The pseudocode - Binary Search - The Algorithm: “check the middle and half the search space” - The pseudocode - Bubble Sort Analysis - Time Complexity: O(n2) - Space Complexity: O(1) - When should you use Bubble Sort? - Selection Sort Analysis - Selection Sort JS Implementation - Time Complexity Analysis - Space Complexity Analysis: O(1) - When should we use Selection Sort? - Insertion Sort Analysis - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - When should you use Insertion Sort? - Merge Sort Analysis - Full code - Merging two sorted arrays - Divide and conquer, step-by-step - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - Quick Sort Analysis - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - Binary Search Analysis - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - Practice: Bubble Sort - Practice: Selection Sort - Practice: Insertion Sort - Practice: Merge Sort - Practice: Quick Sort - Practice: Binary Search

Lists, Stacks, and Queues - Linked Lists - What is a Linked List? - Types of Linked Lists - Linked List Methods - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - Time Complexity - Access and Search - Time Complexity - Insertion and Deletion - Space Complexity - Stacks and Queues - What is a Stack? - What is a Queue? - Stack and Queue Properties - Stack Methods - Queue Methods - Time and Space Complexity Analysis - When should we use Stacks and Queues? -

Graphs and Heaps - Introduction to Heaps - Binary Heap Implementation - Heap Sort - In-Place Heap Sort -

The objective of this lesson is get you comfortable with identifying the time and space complexity of code you see. Being able to diagnose time complexity for algorithms is an essential for interviewing software engineers.

At the end of this, you will be able to

At the end of this, you will be able to

The objective of this lesson is to give you a couple of ways to optimize a computation (algorithm) from a higher complexity class to a lower complexity class. Being able to optimize algorithms is an essential for interviewing software engineers.

At the end of this, you will be able to

At the end of this, you will be able to

A lot of algorithms that we use in the upcoming days will use recursion. The next two videos are just helpful reminders about recursion so that you can get that thought process back into your brain.

Colt Steele provides a very nice, non-mathy introduction to Big-O notation. Please watch this so you can get the easy introduction. Big-O is, by its very nature, math based. It’s good to get an understanding before jumping in to math expressions.

Complete Beginner’s Guide to Big O Notation by Colt Steele.

As software engineers, our goal is not just to solve problems. Rather, our goal is to solve problems efficiently and elegantly. Not all solutions are made equal! In this section we’ll explore how to analyze the efficiency of algorithms in terms of their speed (time complexity) and memory consumption (space complexity).

In this article, we’ll use the word efficiency to describe the amount of resources a program needs to execute. The two resources we are concerned with are time and space. Our goal is to minimize the amount of time and space that our programs use.

When you finish this article you will be able to:

Let’s begin by understanding what method we should not use when describing the efficiency of our algorithms. Most importantly, we’ll want to avoid using absolute units of time when describing speed. When the software engineer exclaims, “My function runs in 0.2 seconds, it’s so fast!!!”, the computer scientist is not impressed. Skeptical, the computer scientist asks the following questions:

The job of the software engineer is to focus on the software detail and not necessarily the hardware it will run on. Because we can’t answer points 1 and 2 with total certainty, we’ll want to avoid using concrete units like “milliseconds” or “seconds” when describing the efficiency of our algorithms. Instead, we’ll opt for a more abstract approach that focuses on point 3. This means that we should focus on how the performance of our algorithm is affected by increasing the size of the input. In other words, how does our performance scale?

The argument above focuses on time, but a similar argument could also be made for space. For example, we should not analyze our code in terms of the amount of absolute kilobytes of memory it uses, because this is dependent on the programming language.

In Computer Science, we use Big-O notation as a tool for describing the efficiency of algorithms with respect to the size of the input argument(s). We use mathematical functions in Big-O notation, so there are a few big picture ideas that we’ll want to keep in mind:

The first 3 points are conceptual, so they are easy to swallow. However, point 4 is typically the biggest source of confusion when learning the notation. Before we apply Big-O to our code, we’ll need to first understand the underlying math and simplification process.

We want our Big-O notation to describe the performance of our algorithm with respect to the input size and nothing else. Because of this, we should to simplify our Big-O functions using the following rules:

We’ll look at these rules in action, but first we’ll define a few things:

If a function consists of a product of many factors, we drop the factors that don’t depend on the size of the input, n. The factors that we drop are called constant factors because their size remains consistent as we increase the size of the input. The reasoning behind this simplification is that we make the input large enough, the non-constant factors will overshadow the constant ones. Below are some examples:

| Unsimplified | Big-O Simplified |

|---|---|

| T( 5 * n2 ) | O( n2 ) |

| T( 100000 * n ) | O( n ) |

| T( n / 12 ) | O( n ) |

| T( 42 * n * log(n) ) | O( n * log(n) ) |

| T( 12 ) | O( 1 ) |

Note that in the third example, we can simplify

T( n / 12 ) to O( n ) because we can rewrite a

division into an equivalent multiplication. In other words,

T( n / 12 ) = T( 1/12 * n ) = O( n ).

If the function consists of a sum of many terms, we only need to show the term that grows the fastest, relative to the size of the input. The reasoning behind this simplification is that if we make the input large enough, the fastest growing term will overshadow the other, smaller terms. To understand which term to keep, you’ll need to recall the relative size of our common math terms from the previous section. Below are some examples:

| Unsimplified | Big-O Simplified |

|---|---|

| T( n3 + n2 + n ) | O( n3 ) |

| T( log(n) + 2n ) | O( 2n ) |

| T( n + log(n) ) | O( n ) |

| T( n! + 10n ) | O( n! ) |

The product and sum rules are all we’ll need to Big-O simplify any math functions. We just apply the product rule to drop all constants, then apply the sum rule to select the single most dominant term.

| Unsimplified | Big-O Simplified |

|---|---|

| T( 5n2 + 99n ) | O( n2 ) |

| T( 2n + nlog(n) ) | O( nlog(n) ) |

| T( 2n + 5n1000) | O( 2n ) |

Aside: We’ll often omit the multiplication symbol in expressions as a form of shorthand. For example, we’ll write O( 5n2 ) in place of O( 5 * n2 ).

Analyzing the efficiency of our code seems like a daunting task because there are many different possibilities in how we may choose to implement something. Luckily, most code we write can be categorized into one of a handful of common complexity classes. In this reading, we’ll identify the common classes and explore some of the code characteristics that will lead to these classes.

When you finish this reading, you should be able to:

There are seven complexity classes that we will encounter most often. Below is a list of each complexity class as well as its Big-O notation. This list is ordered from smallest to largest. Bear in mind that a “more efficient” algorithm is one with a smaller complexity class, because it requires fewer resources.

| Big-O | Complexity Class Name |

|---|---|

| O(1) | constant |

| O(log(n)) | logarithmic |

| O(n) | linear |

| O(n * log(n)) | loglinear, linearithmic, quasilinear |

| O(nc) - O(n2), O(n3), etc. | polynomial |

| O(cn) - O(2n), O(3n), etc. | exponential |

| O(n!) | factorial |

There are more complexity classes that exist, but these are most common. Let’s take a closer look at each of these classes to gain some intuition on what behavior their functions define. We’ll explore famous algorithms that correspond to these classes further in the course.

For simplicity, we’ll provide small, generic code examples that illustrate the complexity, although they may not solve a practical problem.

Constant complexity means that the algorithm takes roughly the same number of steps for any size input. In a constant time algorithm, there is no relationship between the size of the input and the number of steps required. For example, this means performing the algorithm on a input of size 1 takes the same number of steps as performing it on an input of size 128.

The table below shows the growing behavior of a constant function. Notice that the behavior stays constant for all values of n.

| n | O(1) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1 |

| 2 | ~1 |

| 3 | ~1 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~1 |

Below is are two examples of functions that have constant runtimes.

The runtime of the constant1 function does not depend on the

size of the input, because only two arithmetic operations (multiplication

and addition) are always performed. The runtime of the

constant2 function also does not depend on the size of the

input because one-hundred iterations are always performed, irrespective of

the input.

Typically, the hidden base of O(log(n)) is 2, meaning O(log2(n)). Logarithmic complexity algorithms will usual display a sense of continually “halving” the size of the input. Another tell of a logarithmic algorithm is that we don’t have to access every element of the input. O(log2(n)) means that every time we double the size of the input, we only require one additional step. Overall, this means that a large increase of input size will increase the number of steps required by a small amount.

The table below shows the growing behavior of a logarithmic runtime function. Notice that doubling the input size will only require only one additional “step”.

| n | O(log2(n)) |

|---|---|

| 2 | ~1 |

| 4 | ~2 |

| 8 | ~3 |

| 16 | ~4 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~7 |

Below is an example of two functions with logarithmic runtimes.

The logarithmic1 function has O(log(n)) runtime because the

recursion will half the argument, n, each time. In other words, if we pass

8 as the original argument, then the recursive chain would be 8 -> 4

-> 2 -> 1. In a similar way, the logarithmic2 function

has O(log(n)) runtime because of the number of iterations in the while

loop. The while loop depends on the variable i, which will be

divided in half each iteration.

Linear complexity algorithms will access each item of the input “once” (in the Big-O sense). Algorithms that iterate through the input without nested loops or recurse by reducing the size of the input by “one” each time are typically linear.

The table below shows the growing behavior of a linear runtime function. Notice that a change in input size leads to similar change in the number of steps.

| n | O(n) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1 |

| 2 | ~2 |

| 3 | ~3 |

| 4 | ~4 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~128 |

Below are examples of three functions that each have linear runtime.

The linear1 function has O(n) runtime because the for loop

will iterate n times. The linear2 function has O(n) runtime

because the for loop iterates through the array argument. The

linear3 function has O(n) runtime because each subsequent

call in the recursion will decrease the argument by one. In other words,

if we pass 8 as the original argument to linear3, the

recursive chain would be 8 -> 7 -> 6 -> 5 -> … -> 1.

This class is a combination of both linear and logarithmic behavior, so features from both classes are evident. Algorithms the exhibit this behavior use both recursion and iteration. Typically, this means that the recursive calls will halve the input each time (logarithmic), but iterations are also performed on the input (linear).

The table below shows the growing behavior of a loglinear runtime function.

| n | O(n * log2(n)) |

|---|---|

| 2 | ~2 |

| 4 | ~8 |

| 8 | ~24 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~896 |

Below is an example of a function with a loglinear runtime.

The loglinear function has O(n * log(n)) runtime because the

for loop iterates linearly (n) through the input and the recursive chain

behaves logarithmically (log(n)).

Polynomial complexity refers to complexity of the form O(nc) where

n is the size of the input and c is some fixed

constant. For example, O(n3) is a larger/worse function than O(n2), but

they belong to the same complexity class. Nested loops are usually the

indicator of this complexity class.

Below are tables showing the growth for O(n2) and O(n3).

| n | O(n2) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1 |

| 2 | ~4 |

| 3 | ~9 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~16,384 |

| n | O(n3) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1 |

| 2 | ~8 |

| 3 | ~27 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~2,097,152 |

Below are examples of two functions with polynomial runtimes.

The quadratic function has O(n2) runtime because there are

nested loops. The outer loop iterates n times and the inner loop iterates

n times. This leads to n * n total number of iterations. In a similar way,

the cubic function has O(n3) runtime because it has triply

nested loops that lead to a total of n * n * n iterations.

Exponential complexity refers to Big-O functions of the form O(cn) where

n is the size of the input and c is some fixed

constant. For example, O(3n) is a larger/worse function than O(2n), but

they both belong to the exponential complexity class. A common indicator

of this complexity class is recursive code where there is a constant

number of recursive calls in each stack frame. The c will be

the number of recursive calls made in each stack frame. Algorithms with

this complexity are considered quite slow.

Below are tables showing the growth for O(2n) and O(3n). Notice how these grow large, quickly.

| n | O(2n) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~2 |

| 2 | ~4 |

| 3 | ~8 |

| 4 | ~16 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~3.4028 * 1038 |

| n | O(3n) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~3 |

| 2 | ~9 |

| 3 | ~27 |

| 3 | ~81 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~1.1790 * 1061 |

Below are examples of two functions with exponential runtimes.

The exponential2n function has O(2n) runtime because each

call will make two more recursive calls. The

exponential3n function has O(3n) runtime because each call

will make three more recursive calls.

Recall that n! = (n) * (n - 1) * (n - 2) * ... * 1. This

complexity is typically the largest/worst that we will end up

implementing. An indicator of this complexity class is recursive code that

has a variable number of recursive calls in each stack frame. Note that

factorial is worse than exponential because

factorial algorithms have a variable amount of recursive

calls in each stack frame, whereas exponential algorithms have a

constant amount of recursive calls in each frame.

Below is a table showing the growth for O(n!). Notice how this has a more aggressive growth than exponential behavior.

| n | O(n!) |

|---|---|

| 1 | ~1 |

| 2 | ~2 |

| 3 | ~6 |

| 4 | ~24 |

| … | … |

| 128 | ~3.8562 * 10215 |

Below is an example of a function with factorial runtime.

The factorial function has O(n!) runtime because the code is

recursive but the number of recursive calls made in a single

stack frame depends on the input. This contrasts with an

exponential function because exponential functions have a

fixed number of calls in each stack frame.

You may it difficult to identify the complexity class of a given code snippet, especially if the code falls into the loglinear, exponential, or factorial classes. In the upcoming videos, we’ll explain the analysis of these functions in greater detail. For now, you should focus on the relative order of these seven complexity classes!

In this reading, we listed the seven common complexity classes and saw some example code for each. In order of ascending growth, the seven classes are:

Recursion is the root of computation since it trades description for time.—Alan Perlis, Epigrams in Programming

In Arrays and Destructuring Arguments, we worked with the basic idea that putting an array together with a literal array expression was the reverse or opposite of taking it apart with a destructuring assignment.

We saw that the basic idea that putting an array together with a literal array expression was the reverse or opposite of taking it apart with a destructuring assignment.

Let’s be more specific. Some data structures, like lists, can obviously be seen as a collection of items. Some are empty, some have three items, some forty-two, some contain numbers, some contain strings, some a mixture of elements, there are all kinds of lists.

But we can also define a list by describing a rule for building lists. One of the simplest, and longest-standing in computer science, is to say that a list is:

Let’s convert our rules to array literals. The first rule is simple:

[] is a list. How about the second rule? We can express that

using a spread. Given an element e and a list

list , [e, ...list] is a list. We can test this

manually by building up a list:

Thanks to the parallel between array literals + spreads with destructuring + rests, we can also use the same rules to decompose lists:

For the purpose of this exploration, we will presume the following:1

Armed with our definition of an empty list and with what we’ve already

learned, we can build a great many functions that operate on arrays. We

know that we can get the length of an array using its

.length . But as an exercise, how would we write a

length function using just what we have already?

First, we pick what we call a terminal case. What is the length

of an empty array? 0 . So let’s start our function with the

observation that if an array is empty, the length is 0 :

We need something for when the array isn’t empty. If an array is not

empty, and we break it into two pieces, first and

rest , the length of our array is going to be

length(first) + length(rest) . Well, the length of

first is 1 , there’s just one element at the

front. But we don’t know the length of rest . If only there

was a function we could call… Like length !

Let’s try it!

Our length function is recursive, it calls itself.

This makes sense because our definition of a list is recursive, and if a

list is self-similar, it is natural to create an algorithm that is also

self-similar.

“Recursion” sometimes seems like an elaborate party trick. There’s even a joke about this:

When promising students are trying to choose between pure mathematics and applied engineering, they are given a two-part aptitude test. In the first part, they are led to a laboratory bench and told to follow the instructions printed on the card. They find a bunsen burner, a sparker, a tap, an empty beaker, a stand, and a card with the instructions “boil water.”

Of course, all the students know what to do: They fill the beaker with water, place the stand on the burner and the beaker on the stand, then they turn the burner on and use the sparker to ignite the flame. After a bit the water boils, and they turn off the burner and are lead to a second bench.

Once again, there is a card that reads, “boil water.” But this time, the beaker is on the stand over the burner, as left behind by the previous student. The engineers light the burner immediately. Whereas the mathematicians take the beaker off the stand and empty it, thus reducing the situation to a problem they have already solved.

There is more to recursive solutions that simply functions that invoke themselves. Recursive algorithms follow the “divide and conquer” strategy for solving a problem:

The big elements of divide and conquer are a method for decomposing a problem into smaller problems, a test for the smallest possible problem, and a means of putting the pieces back together. Our solutions are a little simpler in that we don’t really break a problem down into multiple pieces, we break a piece off the problem that may or may not be solvable, and solve that before sticking it onto a solution for the rest of the problem.

This simpler form of “divide and conquer” is called linear recursion. It’s very useful and simple to understand. Let’s take another example. Sometimes we want to flatten an array, that is, an array of arrays needs to be turned into one array of elements that aren’t arrays.2

We already know how to divide arrays into smaller pieces. How do we decide whether a smaller problem is solvable? We need a test for the terminal case. Happily, there is something along these lines provided for us:

The usual “terminal case” will be that flattening an empty array will produce an empty array. The next terminal case is that if an element isn’t an array, we don’t flatten it, and can put it together with the rest of our solution directly. Whereas if an element is an array, we’ll flatten it and put it together with the rest of our solution.

So our first cut at a flatten function will look like this:

Once again, the solution directly displays the important elements: Dividing a problem into subproblems, detecting terminal cases, solving the terminal cases, and composing a solution from the solved portions.

Another common problem is applying a function to every element of an array. JavaScript has a built-in function for this, but let’s write our own using linear recursion.

If we want to square each number in a list, we could write:

And if we wanted to “truthify” each element in a list, we could write:

This specific case of linear recursion is called “mapping,” and it is not necessary to constantly write out the same pattern again and again. Functions can take functions as arguments, so let’s “extract” the thing to do to each element and separate it from the business of taking an array apart, doing the thing, and putting the array back together.

Given the signature:

We can write it out using a ternary operator. Even in this small function, we can identify the terminal condition, the piece being broken off, and recomposing the solution.

With the exception of the length example at the beginning,

our examples so far all involve rebuilding a solution using spreads. But

they needn’t. A function to compute the sum of the squares of a list of

numbers might look like this:

There are two differences between sumSquares and our maps

above:

0 instead of an empty list, and;

sumSquares to the rest of the elements.

Let’s rewrite mapWith so that we can use it to sum squares.

And now we supply a function that does slightly more than our mapping functions:

Our foldWith function is a generalization of our

mapWith function. We can represent a map as a fold, we just

need to supply the array rebuilding code:

And if we like, we can write mapWith using

foldWith :

And to return to our first example, our version of length can

be written as a fold:

Linear recursion is a basic building block of algorithms. Its basic form parallels the way linear data structures like lists are constructed: This helps make it understandable. Its specialized cases of mapping and folding are especially useful and can be used to build other functions. And finally, while folding is a special case of linear recursion, mapping is a special case of folding.

undefined as a value, but we are not going to see that in

our examples. A more robust implementation would be

(array) => array.length === 0 , but we are doing

backflips to keep this within a very small and contrived playground.↩

flatten is a very simple

unfold, a

function that takes a seed value and turns it into an array. Unfolds can

be thought of a “path” through a data structure, and flattening a tree

is equivalent to a depth-first traverse.↩

Memoization is a design pattern used to reduce the overall number of calculations that can occur in algorithms that use recursive strategies to solve.

Recall that recursion solves a large problem by dividing it into smaller sub-problems that are more manageable. Memoization will store the results of the sub-problems in some other data structure, meaning that you avoid duplicate calculations and only “solve” each subproblem once. There are two features that comprise memoization:

This is a trade-off between the time it takes to run an algorithm (without memoization) and the memory used to run the algorithm (with memoization). Usually memoization is a good trade-off when dealing with large data or calculations.

You cannot always apply this technique to recursive problems. The problem must have an “overlapping subproblem structure” for memoization to be effective.

Here’s an example of a problem that has such a structure:

Using pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters, what is the smallest combination of coins that total 27 cents?

You’ll explore this exact problem in depth later on. For now, here is some food for thought. Along the way to calculating the smallest coin combination of 27 cents, you should also calculate the smallest coin combination of say, 25 cents as a component of that problem. This is the essence of an overlapping subproblem structure.

Here’s an example of a function that computes the factorial of the number passed into it.

From this plain factorial above, it is clear that every time

you call factorial(6) you should get the same result of

720 each time. The code is somewhat inefficient because you

must go down the full recursive stack for each top level call to

factorial(6). It would be great if you could store the result

of factorial(6) the first time you calculate it, then on

subsequent calls to factorial(6) you simply fetch the stored

result in constant time. You can accomplish exactly this by memoizing with

an object!

The memo object above will map an argument of

factorial to its return value. That is, the keys will be

arguments and their values will be the corresponding results returned. By

using the memo, you are able to avoid duplicate recursive calls!

Here’s some food for thought: By the time your first call to

factorial(6) returns, you will not have just the argument

6 stored in the memo. Rather, you will have

all arguments 2 to 6 stored in the memo.

Hopefully you sense the efficiency you can get by memoizing your functions, but maybe you are not convinced by the last example for two reasons:

Both of those points are true, so take a look at a more advanced example that benefits from memoization.

Here’s a naive implementation of a function that calculates the Fibonacci number for a given input.

Before you optimize this, ask yourself what complexity class it falls into in the first place.

The time complexity of this function is not super intuitive to describe because the code branches twice recursively. Fret not! You’ll find it useful to visualize the calls needed to do this with a tree. When reasoning about the time complexity for recursive functions, draw a tree that helps you see the calls. Every node of the tree represents a call of the recursion:

fib_tree

In general, the height of this tree will be n. You derive

this by following the path going straight down the left side of the tree.

You can also see that each internal node leads to two more nodes. Overall,

this means that the tree will have roughly 2n nodes which is the same as

saying that the fib function has an exponential time

complexity of 2n. That is very slow! See for yourself, try running

fib(50) - you’ll be waiting for quite a while (it took 3

minutes on the author’s machine).

Okay. So the fib function is slow. Is there anyway to speed

it up? Take a look at the tree above. Can you find any repetitive regions

of the tree?

fib_tree_duplicates

As the n grows bigger, the number of duplicate sub-trees

grows exponentially. Luckily you can fix this using memoization by using a

similar object strategy as before. You can use some JavaScript default

arguments to clean things up:

The code above can calculate the 50th Fibonacci number almost instantly!

Thanks to the memo object, you only need to explore a subtree

fully once. Visually, the fastFib recursion has this

structure:

fib_memoized

You can see the marked nodes (function calls) that access the memo in

green. It’s easy to see that this version of the Fibonacci generator will

do far less computations as n grows larger! In fact, this

memoization has brought the time complexity down to linear

O(n) time because the tree only branches on the left side.

This is an enormous gain if you recall the complexity class hierarchy.

Now that you understand memoization, when should you apply it? Memoization is useful when attacking recursive problems that have many overlapping sub-problems. You’ll find it most useful to draw out the visual tree first. If you notice duplicate sub-trees, time to memoize. Here are the hard and fast rules you can use to memoize a slow function:

You learned a secret to possibly changing an algorithm of one complexity class to a lower complexity class by using memory to store intermediate results. This is a powerful technique to use to make sure your programs that must do recursive calculations can benefit from running much faster.

Now that you are familiar with memoization, you can explore a related method of algorithmic optimization: Tabulation. There are two main features that comprise the Tabulation strategy:

Many problems that can be solved with memoization can also be solved with tabulation as long as you convert the recursion to iteration. The first example is the canonical example of recursion, calculating the Fibonacci number for an input. However, in the example, you’ll see the iteration version of it for a fresh start!

Tabulation is all about creating a table (array) and filling it out with elements. In general, you will complete the table by filling entries from “left to right”. This means that the first entry of the table (first element of the array) will correspond to the smallest subproblem. Naturally, the final entry of the table (last element of the array) will correspond to the largest problem, which is also the final answer.

Here’s a way to use tabulation to store the intermediary calculations so that later calculations can refer back to the table.

When you initialized the table and seeded the first two values, it looked like this:

| i | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

table[i] |

0 |

1 |

After the loop finishes, the final table will be:

| i | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

table[i] |

0 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

8 |

13 |

Similar to the previous memo, by the time the function

completes, the table will contain the final solution as well

as all sub-solutions calculated along the way.

To compute the complexity class of this tabulatedFib is very

straightforward since the code is iterative. The dominant operation in the

function is the loop used to fill out the entire table. The length of the

table is roughly n elements long, so the algorithm will have

an O(n) runtime. The space taken by our algorithm is also

O(n) due to the size of the table. Overall, this should be a

satisfying solution for the efficiency of the algorithm.

You may notice that you can cut down on the space used by the function. At any point of the loop, the calculation really only need the previous two subproblems’ results. There is little utility to storing the full array. This refactor is easy to do by using two variables:

Bam! You now have O(n) runtime and O(1) space. This is the most optimal algorithm for calculating a Fibonacci number. Note that this strategy is a pared down form of tabulation, since it uses only the last two values.

Here are the general guidelines for implementing the tabulation strategy. This is just a general recipe, so adjust for taste depending on your problem:

You learned another way of possibly changing an algorithm of one complexity class to a lower complexity class by using memory to store intermediate results. This is a powerful technique to use to make sure your programs that must do iterative calculations can benefit from running much faster.

Consider the following search algorithm known as linear search.

Most Big-O analysis is done on the “worst-case scenario” and provides an upper bound. In the worst case analysis, you calculate the upper bound on running time of an algorithm. You must know the case that causes the maximum number of operations to be executed.

For linear search, the worst case happens when the element to be

searched (term in the above code) is not present in the

array. When term is not present, the

search function compares it with all the elements of

array one by one. Therefore, the worst-case time complexity

of linear search would be O(n).

Consider the following search algorithm known as the binary search. This kind of search only works if the array is already sorted.

For the binary search, you cut the search space in half every time. This means that it reduces the number of searches you must do by half, every time. That means the number of steps it takes to get to the desired item (if it exists in the array), in the worst case takes the same amount of steps for every number within a range defined by the powers of 2.

So, for any number of items in the sorted array between 2n-1 and 2n, it takes n number of steps. That means if you have k items in the array, then it will take log2k.

Binary searches are O(log2n).

Consider the following divide-and-conquer sort method known as the merge sort.

For the merge sort, you cut the sort space in half every time. In each of those halves, you have to loop through the number of items in the array. That means that, for the worst case, you get that same log2n but it must be multiplied by the number of elements in the array, n.

Merge sorts are O(n*log2n).

Consider the following sort algorithm known as the bubble sort.

For the bubble sort, the worst case is the same as the best case because it always makes nested loops. So, the outer loop loops the number of times of the items in the array. For each one of those loops, the inner loop loops again a number of times for the items in the array. So, if there are n values in the array, then a loop inside a loop is n * n. So, this is O(n2). That’s polynomial, which ain’t that good.

use the LeetCode platform to check your work rather than relying on local mocha tests. If you don’t already have an account at LeetCode.com, please click https://leetcode.com/accounts/signup/ to sign up for a free account.

After you sign up for the account, please verify the account with the email address that you used so that you can actually run your solution on LeetCode.com.

In the projects, you will see files that are named “leet_code_«number».js”. When you open those, you will see a link in the file that you can use to go directly to the corresponding problem on LeetCode.com.

Use the local JavaScript file in Visual Studio Code to collaborate on the solution. Then, you can run the proposed solution in the LeetCode.com code runner to validate its correctness.

This project contains two test-driven problems and one problem on LeetCode.com.

cd into the project foldernpm install to install dependencies in the project root

directory

npx test to run the specs/test/test.js. Your job is

to write code in the /lib files to pass all specs.

problems.js, you will write code to make the

lucasNumberMemo and minChange functions

pass.

leet_code_518.js, you will use that file as a

scratch pad to work on the LeetCode.com problem at

https://leetcode.com/problems/coin-change-2/.

This project contains two test-driven problems and one problem on LeetCode.com.

cd into the project foldernpm install to install dependencies in the project root

directory

npx test to run the specs/test/test.js. Your job is

to write code in the /lib files to pass all specs.

problems.js, you will write code to make the

stepper, maxNonAdjacentSum, and

minChange functions pass.

leet_code_64.js, you will use that file as a scratch

pad to work on the LeetCode.com problem at

https://leetcode.com/problems/minimum-path-sum/.

leet_code_70.js, you will use that file as a scratch

pad to work on the LeetCode.com problem at

https://leetcode.com/problems/climbing-stairs/.

The objective of this lesson is for you to get experience implementing common sorting algorithms that will come up during a lot of interviews. It is also important for you to understand how different sorting algorithms behave when given output.

At the end of this, you will be able to

bubble sort on an array of numbers.

selection sort on an array of numbers.

insertion sort on an array of numbers.

merge sort on an array of numbers.

quick sort on an array of numbers.

At the end of this, you will be able to

bubble sort on an array of numbers.

selection sort on an array of numbers.

insertion sort on an array of numbers.

merge sort on an array of numbers.

quick sort on an array of numbers.

Bubble Sort is generally the first major sorting algorithm to come up in most introductory programming courses. Learning about this algorithm is useful educationally, as it provides a good introduction to the challenges you face when tasked with converting unsorted data into sorted data, such as conducting logical comparisons, making swaps while iterating, and making optimizations. It’s also quite simple to implement, and can be done quickly.

Bubble Sort is almost never a good choice in production. simply because:

It is quite useful as an educational base for you, and as a conversational base for you while interviewing, because you can discuss how other more elegant and efficient algorithms improve upon it. Taking naive code and improving upon it by weighing the technical tradeoffs of your other options is 100% the name of the game when trying to level yourself up from a junior engineer to a senior engineer.

As you progress through the algorithms and data structures of this course, you’ll eventually notice that there are some recurring funny terms. “Bubbling up” is one of those terms.

When someone writes that an item in a collection “bubbles up,” you should infer that:

When invoking Bubble Sort to sort an array of integers in ascending order, the largest integers will “bubble up” to the “top” (the end) of the array, one at a time.

The largest values are captured, put into motion in the direction defined by the desired sort (ascending right now), and traverse the array until they arrive at their end destination. See if you can observe this behavior in the following animation (courtesy http://visualgo.net):

bubble sort

As the algorithm iterates through the array, it compares each element to the element’s right neighbor. If the current element is larger than its neighbor, the algorithm swaps them. This continues until all elements in the array are sorted.

Bubble sort works by performing multiple passes to move elements closer to their final positions. A single pass will iterate through the entire array once.

A pass works by scanning the array from left to right, two elements at a time, and checking if they are ordered correctly. To be ordered correctly the first element must be less than or equal to the second. If the two elements are not ordered properly, then we swap them to correct their order. Afterwards, it scans the next two numbers and continue repeat this process until we have gone through the entire array.

See one pass of bubble sort on the array [2, 8, 5, 2, 6]. On

each step the elements currently being scanned are in

bold.

Because at least one swap occurred, the algorithm knows that it wasn’t sorted. It needs to make another pass. It starts over again at the first entry and goes to the next-to-last entry doing the comparisons, again. It only needs to go to the next-to-last entry because the previous “bubbling” put the largest entry in the last position.

Because at least one swap occurred, the algorithm knows that it wasn’t sorted. Now, it can bubble from the first position to the last-2 position because the last two values are sorted.

No swap occurred, so the Bubble Sort stops.

During Bubble Sort, you can tell if the array is in sorted order by checking if a swap was made during the previous pass performed. If a swap was not performed during the previous pass, then the array must be totally sorted and the algorithm can stop.

You’re probably wondering why that makes sense. Recall that a pass of Bubble Sort checks if any adjacent elements are out of order and swaps them if they are. If we don’t make any swaps during a pass, then everything must be already in order, so our job is done. Let that marinate for a bit.

Selection Sort is very similar to Bubble Sort. The major difference between the two is that Bubble Sort bubbles the largest elements up to the end of the array, while Selection Sort selects the smallest elements of the array and directly places them at the beginning of the array in sorted position. Selection sort will utilize swapping just as bubble sort did. Let’s carefully break this sorting algorithm down.

Selection sort works by maintaining a sorted region on the left side of the input array; this sorted region will grow by one element with every “pass” of the algorithm. A single “pass” of selection sort will select the next smallest element of unsorted region of the array and move it to the sorted region. Because a single pass of selection sort will move an element of the unsorted region into the sorted region, this means a single pass will shrink the unsorted region by 1 element whilst increasing the sorted region by 1 element. Selection sort is complete when the sorted region spans the entire array and the unsorted region is empty!

selection sort

The algorithm can be summarized as the following:

In pseudocode, the Selection Sort can be written as this.

With Bubble Sort and Selection Sort now in your tool box, you’re starting to get some experience points under your belt! Time to learn one more “naive” sorting algorithm before you get to the efficient sorting algorithms.

Insertion Sort is similar to Selection Sort in that it gradually builds up a larger and larger sorted region at the left-most end of the array.

However, Insertion Sort differs from Selection Sort because this algorithm does not focus on searching for the right element to place (the next smallest in our Selection Sort) on each pass through the array. Instead, it focuses on sorting each element in the order they appear from left to right, regardless of their value, and inserting them in the most appropriate position in the sorted region.

See if you can observe the behavior described above in the following animation:

insertion sort

Insertion Sort grows a sorted array on the left side of the input array by:

These steps are easy to confuse with selection sort, so you’ll want to watch the video lecture and drawing that accompanies this reading as always!

You’ve explored a few sorting algorithms already, all of them being quite slow with a runtime of O(n2). It’s time to level up and learn your first time-efficient sorting algorithm! You’ll explore merge sort in detail soon, but first, you should jot down some key ideas for now. The following points are not steps to an algorithm yet; rather, they are ideas that will motivate how you can derive this algorithm.

You’re going to need a helper function that solves the first major point

from above. How might you merge two sorted arrays? In other words you want

a merge function that will behave like so:

Once you have that, you get to the “divide and conquer” bit.

The algorithm for merge sort is actually really simple.

The process is visualized below. When elements are moved to the bottom of

the picture, they are going through the merge step:

merge sort

The pseudocode for the algorithm is as follows.

Quick Sort has a similar “divide and conquer” strategy to Merge Sort. Here are a few key ideas that will motivate the design:

Regarding that first point, for example given

[7, 3, 8, 9, 2] and a target of 5, we know

[3, 2] are numbers less than 5 and

[7, 8, 9] are numbers greater than 5.

In general, the strategy is to divide the input array into two subarrays: one with the smaller elements, and one with the larger elements. Then, it recursively operates on the two new subarrays. It continues this process until of dividing into smaller arrays until it reaches subarrays of length 1 or smaller. As you have seen with Merge Sort, arrays of such length are automatically sorted.

The steps, when discussed on a high level, are simple:

Before we move forward, see if you can observe the behavior described above in the following animation:

quick sort

Formally, we want to partition elements of an array relative to a pivot value. That is, we want elements less than the pivot to be separated from elements that are greater than or equal to the pivot. Our goal is to create a function with this behavior:

Seems simple enough! Let’s implement it in JavaScript:

You don’t have to use an explicit partition helper function

in your Quick Sort implementation; however, we will borrow heavily from

this pattern. As you design algorithms, it helps to think about key

patterns in isolation, although your solution may not feature that exact

helper. Some would say we like to divide and conquer.

It is so small, this algorithm. It’s amazing that it performs so well with so little code!

We’ve explored many ways to sort arrays so far, but why did we go through

all of that trouble? By sorting elements of an array, we are organizing

the data in a way that gives us a quick way to look up elements later on.

For simplicity, we have been using arrays of numbers up until this point.

However, these sorting concepts can be generalized to other data types.

For example, it would be easy to modify our comparison-based sorting

algorithms to sort strings: instead of leveraging facts like

0 < 1, we can say 'A' < 'B'.

Think of a dictionary. A dictionary contains alphabetically sorted words and their definitions. A dictionary is pretty much only useful if it is ordered in this way. Let’s say you wanted to look up the definition of “stupendous.” What steps might you take?

You are essentially using the binarySearch algorithm in the

real world.

Formally, our binarySearch will seek to solve the following

problem:

Programmatically, we want to satisfy the following behavior:

Before we move on, really internalize the fact that

binarySearch will only work on

sorted arrays! Obviously we can search any array, sorted

or unsorted, in O(n) time. But now our goal is be able to

search the array with a sub-linear time complexity (less than

O(n)).

Bubble Sort manipulates the array by swapping the position of two elements. To implement Bubble Sort in JS, you’ll need to perform this operation. It helps to have a function to do that. A key detail in this function is that you need an extra variable to store one of the elements since you will be overwriting them in the array:

Note that the swap function does not create or return a new array. It mutates the original array:

Take a look at the snippet below and try to understand how it corresponds to the conceptual understanding of the algorithm. Scroll down to the commented version when you get stuck.